Peter Mills – Senior Manager

There are a range of circumstances where two or more shareholders would decide to part ways and a common course of action in that case is a demerger. The relevant tax rules are complex but a range of reliefs are available to preserve tax neutrality (or close to) in these scenarios and therefore, subject to careful structuring, different groups of shareholders can generally each take a part of the business with minimal immediate tax exposures.

Demergers in practice?

There are various approaches to separating a business but two of the most common approaches – particularly where non-trading assets are involved – are ‘capital reduction demergers’ and ‘liquidation demergers’. ‘Capital reduction demergers’ are often the preferred option because they are generally more straightforward to implement and avoid the stigma associated with liquidations.

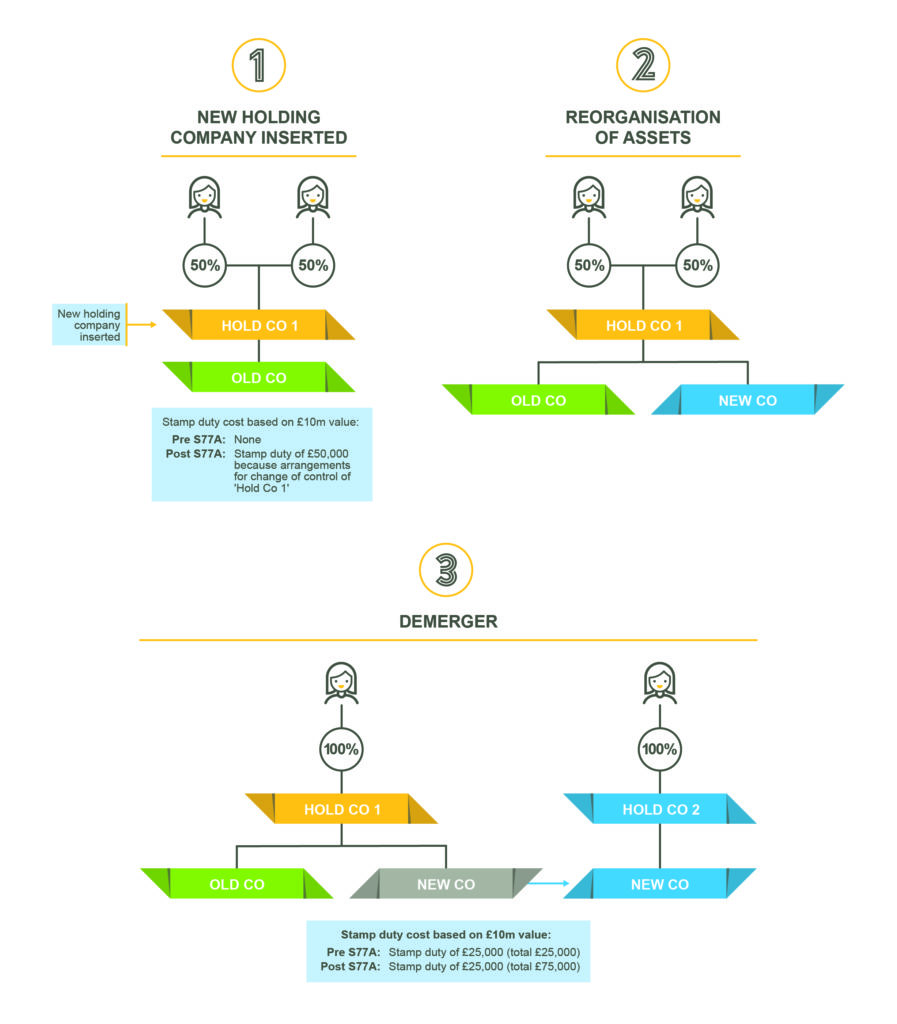

A preliminary stage of most demergers is to insert a new holding company on top of the existing group structure, by share for share exchange, which is then liquidated or reduces its share capital to facilitate the transfer (or retention) of assets between the shareholders. Historically this could have been carried out with no tax cost, including stamp duty, although the unexpected introduction of a ‘dis-qualifying arrangement’ test at S77A FA 1986 in 2016 reared an inadvertent challenge.

This rule prevents stamp duty relief in respect of transactions where arrangements are in place for a person(s) to obtain control of a acquiring company. Should the outcome of a subsequent demerger be that different shareholders end up controlling different groups of assets, stamp duty relief may not be available when the initial holding company is inserted: this is particularly the case with capital reduction demergers.

It’s worth noting that in such transactions, a charge to stamp duty in respect of the demerged assets is often already unavoidable (particularly in light of other changes in Finance Bill 2019-20).

Since the introduction of S77A, parting shareholders have potentially been forced to accept duplicate and seemingly disproportionate tax transaction costs or, due to the way HMRC interprets the definition of a change of control differently in different variations of demerger, to pursue the transaction by way of an alternative liquidation demerger which can bring with it greater complexity, cost and commercial risk. In worst cases, the shareholders may be forced to abandon their plans.

What’s changed?

The Finance Bill 2019-20 contained a welcome relaxation to the stamp duty rules affecting demergers: a relaxation to S77A so that situations where the person(s) gaining control of the company have owned more than 25% for the past three years are essentially disregarded in establishing where there has been a change of control, subject to enactment next year.

This is a positive step and the explanatory notes that accompany the Finance Bill clearly indicate that the changes were drafted with capital reduction demergers in mind. In most cases (the above illustration, for example), the demerger will not be a disqualifying arrangement, restoring flexibility to plan demergers without superfluous tax risks.

Where the drafting is lacking

The above said, there do still appear to be some seemingly arbitrary deficiencies in the drafting and the relaxation will not always provide the protection expected. In some cases it will still not be possible to avoid duplicate stamp duty charges and, whilst these limited circumstances may be more acceptable collateral damage, it’s unclear why any is necessary.

Family-run companies, as well as larger corporates, will often have minority shareholders: perhaps younger generations, employee or investor shareholders or a number of business partners who will not independently own 25% of the shares.

Consider an example of a investment company that is owned by the second and third generations of two founding brothers; those two family units having reached an agreement that they should separate because they have different strategic aspirations which are causing conflict. This separation may not be possible when using a capital reduction demerger without a significant stamp duty exposure, although the brothers themselves could have separated the business before they died resulting in a more efficient outcome despite arguably having less of a commercial reason for doing so.

Another complication can be in the requirement that the relevant shareholders need to have held the requisite 25% for a minimum of three years.

This could be a challenge for a number of reasons: there may have been changes in the shareholders or a prior reconstruction (as circumstances do change after all) meaning the shares have not been held for the prior three years.

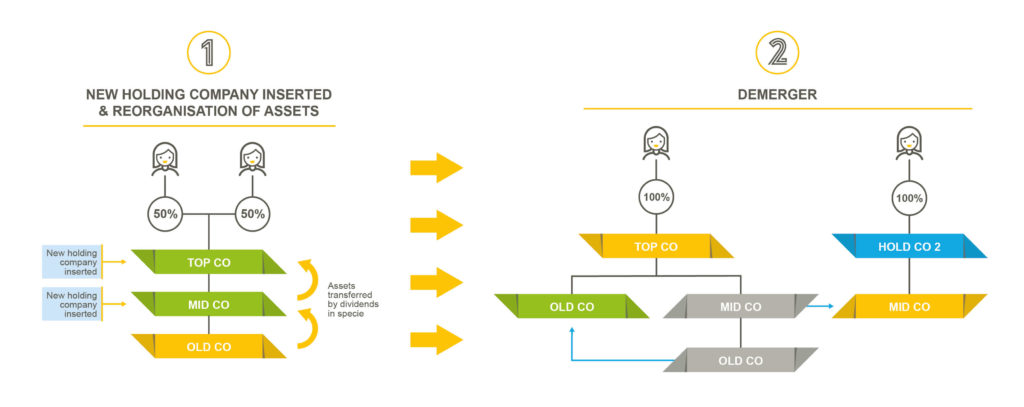

It is also not an uncommon structuring arrangement to insert a number of (rather than a single) new holding companies before undertaking the demerger itself, for example where it’s more desirable to transfer assets between companies by distributions in specie. This can be advantageous to move reserves around the group before separating and also to manage SDLT charges if property is involved. In those cases, the shareholders won’t have held shares in those companies for the necessary three year period such that the successive acquisitions benefit from the new relaxations.

Although these may feel like niche technical examples, every reconstruction is unique and there are always a number of factors and tax risks to balance. The commercial reality of most demergers is that the financial value held by each shareholder in unchanged. No cash is created and any tax charges must be funded by another means. In the most extreme of cases those tax charges can prove prohibitively high.

What now?

The proposed amendment goes some of the way to resolving the inherent challenges in the original drafting of S77A, however it is still unclear why this was allowed to contaminate demerger transactions in the first place. If the intention of this revision is to provide protection in legitimate commercial reorganisations (bearing in mind most of the relevant reliefs have commercial purpose tests anyway), it seems inequitable that multiple stamp duty charges should arise even in obscure scenarios. More flexibility would be preferred. Menzies have commented on HMRC consultation on the proposed changes to encourage a more flexible and commercial set of changes and are hopeful that a more pragmatic approach will be adopted.